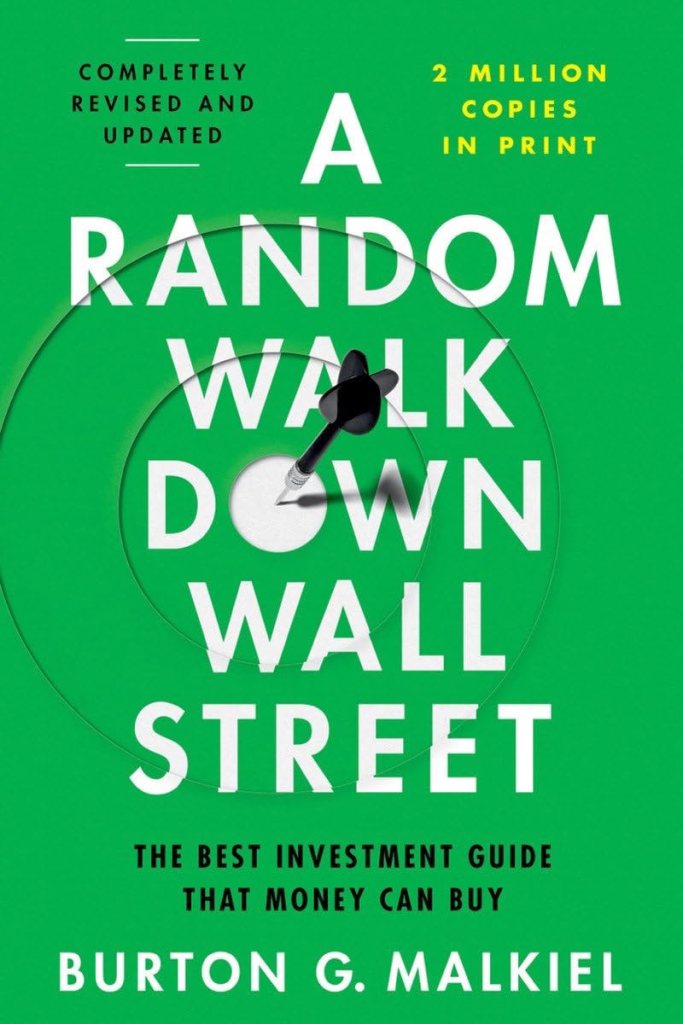

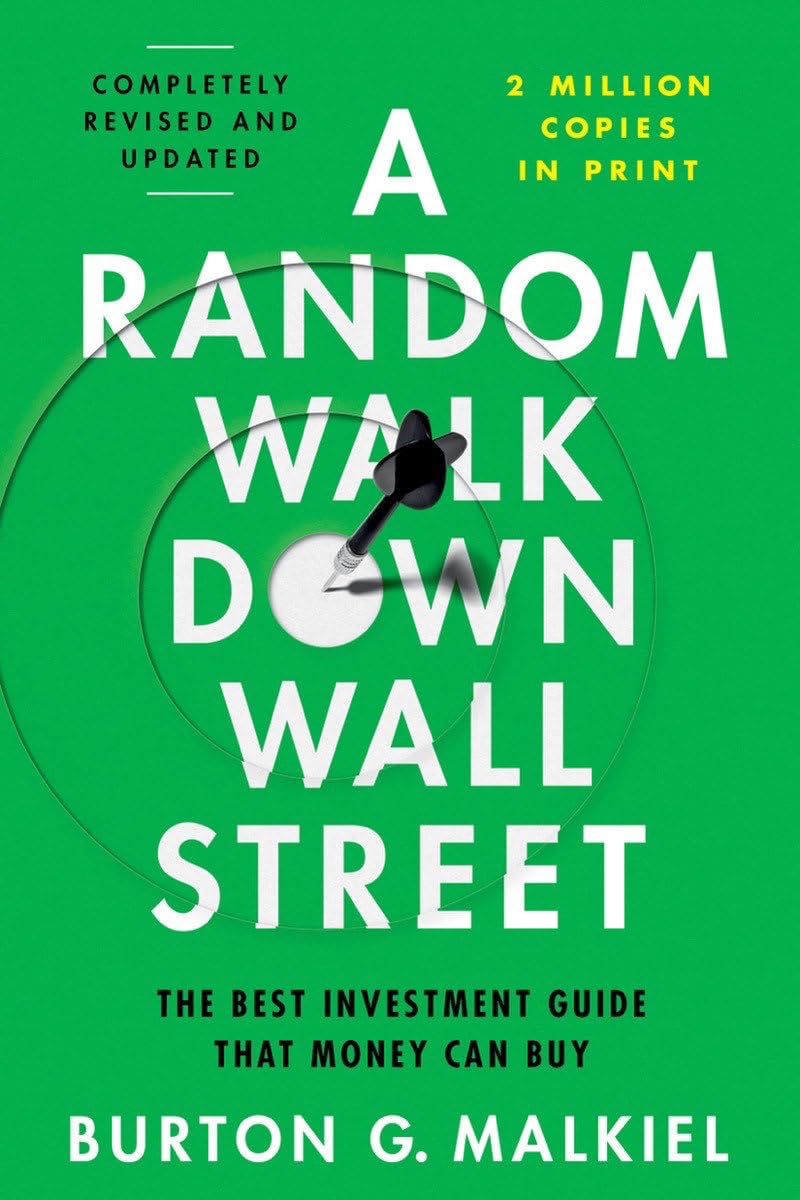

The Random Walk to Wealth: Why Simple Investing Beats the Pros

The world of finance often seems complex, dominated by “experts” armed with sophisticated models, derivative instruments, and high-frequency trading platforms. Many believe the individual investor scarcely stands a chance against Wall Street’s professionals. But nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, adopting a straightforward, “time-tested strategy” can enable you to do as well as the experts—perhaps even better.

This is a guided tour, or “random walk,” down Wall Street, offering practical advice for successful investing. The foundation of this journey rests on understanding what a random walk is and recognizing the deadly lure of speculation.

What is a Random Walk?

When applied to the stock market, a random walk means that short-run changes in stock prices are unpredictable; thus, investment advisory services, complex chart patterns, and earnings forecasts are largely useless. Academics use the term “random walk” to insult professional forecasters. Taken to its logical extreme, the concept suggests that a blindfolded monkey throwing darts at the stock listings could select a portfolio that performs just as well as one selected by the experts.

For those aiming for financial success, it is crucial to understand the distinction between investing and speculating. Investing is purchasing assets to gain profit in the form of reasonably predictable income (such as dividends, interest, or rentals) and/or appreciation over the long term, measured over years or decades. A speculator, conversely, buys stocks hoping for a short-term gain over the next days or weeks. This guide is strictly for investors aiming to get rich slowly but surely.

To navigate the market, investors must understand the two principal approaches to pricing assets: the Firm-Foundation Theory and the Castle-in-the-Air Theory.

The Firm-Foundation Theory posits that every security has an intrinsic value, determined by the present value of its future income stream. This value is based on solid fundamentals, such as expected dividends and the expected growth rate of those dividends. The rational investor calculates this value and buys when the market price falls below it.

In contrast, the Castle-in-the-Air Theory concentrates on psychic values. Articulated by John Maynard Keynes, this theory suggests professional investors focus not on intrinsic value, but on analyzing how the crowd is likely to behave in the future. The successful investor tries to estimate what investment situations are most susceptible to public “castle-building” and buys before the crowd arrives. This is also known as the “greater fool” theory: an investment holds itself up by its own bootstraps because a buyer expects to sell it to someone else at a higher price.

The Madness of Crowds: History’s Warning Labels

History shows that market prices often conform well to the Castle-in-the-Air Theory, making investing extremely dangerous. When greed runs amok, market participants ignore firm foundations of value for the dubious assumption that they can make a killing by building castles in the air.

Speculative Binges Throughout History

- The Tulip-Bulb Craze (17th Century): In Holland, a fascination with tulip bulbs led to a speculative frenzy where prices soared uncontrollably. Trading devices like options leveraged investments, increasing potential rewards and risks, and ensuring broad participation. Eventually, the financial law of gravitation took hold; prices collapsed until bulbs were almost worthless, selling for no more than a common onion.

- The South Sea Bubble (18th Century): In England, the craving for quick fortunes led promoters to flood the market with absurd new issues, offering hope of immense gain, such as a company for “carrying on an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is”. Like bubbles, these promotions popped quickly, usually within a week or so.

- Wall Street Lays an Egg (1920s): The Great Crash of 1929 illustrated how pooled investments artificially manipulated stock prices. The market ignored fundamental business soundness, culminating in catastrophic trading days like Black Thursday and Tuesday, October 29, 1929. By 1932, many blue-chip stocks had fallen 95 percent or more.

- The Growth-Stock/New-Issue Craze (1960s): Companies drastically changed names (e.g., from “Shoelaces, Inc.” to “Electronics and Silicon Furth-Burners”) to attract high price-earnings (P/E) multiples, often leading to spectacular initial gains followed by shares becoming almost worthless within a decade.

- The Conglomerate Boom: Companies literally “manufactured growth” by swapping their high-multiple stock for the stock of another company with a lower multiple, creating artificial earnings per share growth without any underlying business expansion. Wall Street professionals fell for this con game for years.

- The Internet Bubble (Early 2000s): Associated with new technology and massive business opportunities, the Internet spawned the largest creation—and subsequent largest destruction—of stock market wealth ever. Valuation focused on “new metrics” like “eyeballs” (the number of people viewing a website) and “mind share” rather than sales, revenues, or profits. Companies with no revenues or profits, like TheGlobe.com, were brought to market at high prices, which immediately soared. Eventually, investors ran out of “greater fools”. The collapse wiped out over $8 trillion of market value.

- The U.S. Housing Bubble: The bubble in single-family home prices was the biggest U.S. real estate bubble of all time and had far greater significance for average Americans. This bubble was fueled by a new system of banking involving complex derivative securities and looser lending standards (e.g., NINJA—No Income, No Job, No Assets—loans). The crash almost brought down the global financial system.

The lesson is clear: investors must be able to resist being swept up in short, get-rich-quick speculative binges.

The Illusion of Expertise: Why Technical and Fundamental Analysis Fail

Professionals arm themselves against the random-walk onslaught using two primary techniques: technical analysis and fundamental analysis. However, extensive evidence suggests these methods rarely provide a consistent advantage that overcomes transaction costs.

1. Technical Analysis: The Charting Game

Technical analysis (or charting) is the attempt to forecast stock prices by interpreting the patterns and trends visible in past market data and trading volumes.

The core principles are:

- All information is reflected in past market prices and trading volume. A chart already comprises all the necessary fundamental information.

- Prices move in trends. A stock that is rising tends to keep rising; one at rest tends to stay at rest.

The academic world considers technical analysis akin to astrology. Testing of various sophisticated technical systems, such as the Filter System (buy a stock after it moves up a certain percentage, sell after it drops a certain percentage) and Chart Patterns (like “heads and shoulders”) showed that they cannot consistently beat a simple buy-and-hold strategy once transactions charges are factored in.

Why does charting fail? Because the market is highly efficient, and prices rapidly adjust to new information, making past movements useless for predicting future directions. Furthermore, any regularity in the stock market that can be discovered and acted upon profitably is bound to destroy itself as soon as enough people exploit it.

2. Fundamental Analysis: The Clouded Crystal Ball

Fundamental analysis focuses on finding the intrinsic value of a security by carefully studying a company’s financial statements, management, industry prospects, and future growth rates. However, several factors cloud the fundamental analyst’s crystal ball:

- Forecasting Difficulty: Security analysts consistently have enormous difficulty accurately forecasting earnings. Their one-year forecasts have often proved even worse than their five-year projections.

- Creative Accounting: A firm’s income statement can be likened to a bikini—what it reveals is interesting but what it conceals is vital. Companies frequently use “aggressive fictions” and “creative accounting” (or what CEOs call “earnings before I tricked the dumb auditor”) to pump up reported earnings and meet short-term targets desired by Wall Street.

- Conflicts of Interest: Analysts’ salaries have historically been tied not to the quality of their research, but to their ability to steer lucrative investment banking business to their firms. This leads to rampant conflicts, resulting in an overwhelming number of “buy” or “strong buy” recommendations, even for sinking companies.

The Mutual Fund Performance Record

The ultimate test of professional investment advice lies in performance. Studies comparing the average actively managed mutual fund against the Standard & Poor’s 500-Stock Index demonstrate that simply buying and holding the stocks in a broad market index is a strategy that is very hard for the professional portfolio manager to beat.

For example, an investor who put $10,000 into an S&P 500 Index Fund at the start of 1969 would have held a portfolio worth $736,196 by June 2014 (with dividends reinvested), while the average actively managed fund investor would have only seen their investment grow to $501,470.

Furthermore, there is a fundamental lack of persistence in performance. Managers who perform best in one period are often the worst in the next. The few exceptional long-run successes (like Warren Buffett) can often be attributed to chance, given the large number of market players, much like a few coin flippers will inevitably flip ten heads in a row.

The New Investment Technology and Behavioral Traps

Academics developed the New Investment Technology to rationally account for risk, primarily through Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) and the Capital-Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). MPT confirms the time-honored maxim that diversification is a sensible strategy to reduce risk. The theory suggests that holding assets with non-parallel returns (like resort stocks and umbrella manufacturer stocks—one thrives in sun, the other in rain) significantly lowers overall portfolio risk without sacrificing expected return.

Behavioral Finance: The Investor’s Worst Enemy

Behavioral finance studies how investors fail to act rationally. The biggest hurdle for investors is often themselves. Common irrational behaviors and their lessons include:

- Overconfidence: Most investors consider themselves “above average”. This leads to excessive trading, believing they can pick winners or time the market. Excessive trading, however, drastically reduces net returns due to transaction costs and taxes. Lesson: Avoid overtrading and realize your stock-picking skill is likely average.

- Herd Behavior: People tend to follow the crowd, often leading to speculative manias. The desire to fit in or simply assume the crowd knows something you don’t is strong. Lesson: Avoid herd behavior; keep your head when all about you are losing theirs.

- Loss Aversion & Regret: Investors are far more distressed at taking losses than they are overjoyed at realizing gains. This leads to the paradoxical trap of holding onto losers (to avoid admitting a mistake/realizing a loss) while quickly selling winners (to enjoy success). Lesson: Sell losers, not winners, especially in taxable accounts to realize tax benefits.

- Chasing Hot Tips and IPOs: Hot tips are overwhelmingly likely to be the poorest investments of your life, typically involving stocks that promise quick riches but offer high risk. Similarly, the average investor should be wary of Initial Public Offerings (IPOs). The “really good IPOs” are snapped up by institutions, leaving only the “dogs” available for the small investor. Lesson: If it sounds too good to be true (like consistent, moderate, low-volatility returns), it is too good to be true—as demonstrated by the Madoff fraud.

The “Smart Beta” Trap

A new, hotshot investment strategy is called “smart beta,” which seeks to tilt a portfolio toward factors (or “flavors”) that have historically produced greater returns than the broad market, such as Value, Smaller Size, or Low Volatility.

- Value Wins: Focuses on stocks with low P/E ratios and low prices relative to book value. The logic is that investors tend to overpay for speculative “growth” stocks.

- Smaller is Better: Small-company stocks have historically generated larger returns than large-company stocks over long periods.

However, “smart beta” strategies often lead to portfolios that are less diversified, more concentrated in certain sectors (like utilities for low volatility portfolios), and complex, making them unsuitable for the individual investor. The best approach remains using low-cost, broad-based, capitalization-weighted index funds as the core of the portfolio.

A Practical Fitness Manual for Random Walkers

Financial success hinges not on finding the next “hot stock,” but on following basic, disciplined steps.

Exercise 1: Gather the Necessary Supplies (Save!)

The single most important driver in the growth of your assets is how much you save. Without a regular savings program, returns are irrelevant. The secret to getting rich slowly but surely is the miracle of compound interest. Start saving early and save regularly, utilizing dollar-cost averaging (investing a fixed amount regularly, regardless of price fluctuations) to reduce the risk of buying only at temporarily inflated prices.

Exercise 2: Don’t Be Caught Empty-Handed (Reserves and Insurance)

Everyone needs a cash reserve (ideally three months of living expenses) in safe and liquid investments to cope with unexpected needs, such as job loss or major medical bills. Additionally, appropriate insurance is a must, particularly health, disability, and term life insurance for those with dependents. For most people, term insurance, purchased directly without an agent, is preferable to high-premium policies that combine insurance with an expensive investment account.

Exercise 4: Learn How to Dodge the Tax Collector

Maximize savings in tax-advantaged accounts. Utilize Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs), Roth IRAs, and employer-sponsored plans like 401(k)s and 403(b)s. These plans allow funds to grow tax-free, drastically increasing the final accumulated value compared to taxable accounts. For college savings, “529” plans offer federal tax-free growth on investment earnings, provided withdrawals are for qualified higher education purposes.

Exercise 5: Understand Your Investment Objectives (Your Sleeping Point)

You must decide the trade-off you are willing to make between eating well and sleeping well. High investment rewards can be achieved only at the cost of substantial risk-taking. Your required risk level depends heavily on your capacity for risk (related to your age and non-investment income) and your attitude toward risk (your comfort level with market volatility).

A young professional in their twenties has a high capacity for risk due to a long life expectancy and decades of future earning power; thus, an aggressive portfolio is suitable. A sixty-five-year-old retiree has little capacity to absorb losses and needs safe, income-generating investments.

Exercise 6: Begin Your Walk at Your Own Home

Own your own home if you can afford it. Home ownership offers significant tax advantages (deductibility of mortgage interest and property taxes) and is a good way to force yourself to save. Additionally, commercial real estate can be added to a portfolio safely through Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs).

The Life-Cycle Investment Guide

The most important investment decision concerns the balancing of asset categories (asset allocation). More than 90 percent of your total return is determined by this mix. As you age, you must shift your portfolio toward safer assets, decreasing the proportion of stocks and increasing fixed-income and cash holdings.

| Age Group | Stocks (%) | Bonds & Substitutes (%) | Real Estate (%) | Cash (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mid-Twenties | 70% (One-half U.S./One-half International/Emerging) | 15% (Short-term, no-load, high-grade) | 10% (REITs) | 5% |

| Late Sixties and Beyond | 40% (One-half U.S./One-half International/Emerging) | 35% (Short-term, no-load, high-grade) | 15% (REITs) | 10% |

Source: Life-Cycle Investment Guide, summary for illustration only.

Rebalancing annually (bringing asset proportions back in line with targets) can reduce investment risk and possibly increase returns by forcing you to sell high and buy low. Investors who want a set-it-and-forget-it approach can use Life-Cycle Funds, which automatically rebalance and adjust the asset allocation to a safer mix as the target retirement date approaches.

The Three Giant Steps Down Wall Street

How do you implement your equity allocation? There are three ways:

1. The No-Brainer Step: Investing in Index Funds

For most investors, the easiest, lowest-risk, and most effective solution is the No-Brainer Step: invest the core of your portfolio in broad-based index funds or indexed ETFs.

- Index funds (like the Vanguard 500 Index Trust or Total Stock Market funds) simply buy and hold all the stocks in a broad index, providing massive diversification and ruling out extraordinary losses relative to the market.

- Index funds offer extremely low expense ratios (far less than actively managed funds) and are highly tax-efficient. These cost savings accumulate over decades, dramatically increasing net returns.

- The Total Stock Market Index (containing thousands of U.S. companies) is generally preferred over the S&P 500 because it includes smaller, dynamic companies that offer higher investment rewards (along with higher risks).

2. The Do-It-Yourself Step: Potentially Useful Stock-Picking Rules

For those who insist on playing the stock-picking game, focus on the following rules to tilt the odds slightly in your favor:

- Rule 1: Confine stock purchases to companies that appear able to sustain above-average earnings growth for at least five years. Consistent growth is the single most important element contributing to success.

- Rule 2: Never pay more for a stock than can reasonably be justified by a firm foundation of value. Look for “Growth At A Reasonable Price (GARP)”. Avoid high-multiple stocks, where future growth is already discounted, as failure of that growth can lead to heavy losses (both earnings and the multiple drop).

- Rule 3: It helps to buy stocks with the kinds of stories of anticipated growth on which investors can build castles in the air. Successful investing demands both intellectual and psychological acuteness. Buy stocks whose story is likely to catch the fancy of the crowd—but ensure those castles rest on a firm foundation.

- Rule 4: Trade as little as possible. Frequent trading subsidizes your broker and increases your tax burden. Ride the winners. Be merciless with losers, selling them by the end of the year to realize tax-deductible losses that offset capital gains.

3. The Substitute-Player Step: Hiring a Professional

While actively managed mutual funds are numerous, choosing a fund based on its past superior performance is unreliable, as there is no dependable long-term persistence in mutual fund success. To choose a managed fund if you insist on this path, focus on the following criteria:

- Low expense ratios: High management fees drastically reduce net returns.

- Low turnover: High turnover generates unnecessary trading costs and higher tax burdens.

- Use of Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs): ETFs tend to offer lower costs and greater tax efficiency than traditional open-end mutual funds .

A Final Word

The timeless lessons of investing are simple: broad diversification, annual rebalancing, using low-cost index funds, and staying the course. If you follow these basic, simple rules, you are likely to achieve satisfactory returns, even during the toughest of times, and avoid the allure of speculative get-rich-quick schemes that are doomed to failure.

The investment game is fun, but luck is often 99 percent responsible for those who beat the averages. By indexing at least the core of your portfolio, you are guaranteed to play the game at par every round, ensuring you win or at least do not lose too much.

The complexity of the financial market is often compared to a sophisticated casino. However, unlike a casino, the odds are rigged in favor of the patient players who stick to broad diversification and low-cost indexing, while the high-stakes speculators and chartists find themselves playing a losing game against the rapid efficiency of the market.